Posted March 22nd, 2010 at 1:00pm in First Principles, Health Care

In 1774, in response to the first Tea Party, the British Parliament issued a series of acts designed to control the colonists, stop their protests and restrict their liberty. The American colonists called them “The Intolerable Acts.”

What we have all just witnessed in the debate over health care reform, in substance and in process violates our first principles, takes away our independence and undermines the very rule of law. If left standing, this law places us evermore firmly on the course of becoming a heavily centralized European-style nation, stifled by government run health care and ruled more by bureaucrats than elected legislatures. This is not “progress” but the revival of a failed, undemocratic, and illiberal form of statism.

These acts are intolerable.

In 1763, with the British victory over France in the Seven Years’ War (which began in North America as the French and Indian War), Great Britain controlled—in addition to the thirteen American colonies— New France (Canada), Spanish Florida, and all the lands east of the Mississippi River. It also had massive debts, incurred in large part in the defense of that empire, and so the English Parliament looked for the first time to the American colonies as a source of revenue.

The American Revenue Act (sometimes called the Sugar Act) expanded various import and export duties and created additional courts and collection mechanisms to strictly enforce trade laws. Then parliament went a step further and passed the first direct tax levied on America, requiring all newspapers, almanacs, pamphlets, and official documents—even decks of playing cards!—to have stamps (hence it was called the Stamp Act, which was passed 245 years ago today, March 22nd) to show payment of taxes.

The colonists—who by this point were very used to their independence and Britain’s benign oversight of their affairs—were none too pleased with the new imperial policies. Colonial merchants instinctively began a movement to boycott British goods, and a new group called the Sons of Liberty was formed to foment and organize opposition. Several legislatures called for united action, and nine colonies sent delegates to a Stamp Act Congress in New York in October 1765.

The American Revolution began as a tax revolt. But it is important to understand from the start that the debate was never really over the amount of taxation (the taxes were actually quite low) but the process by which the British government imposed and enforced these taxes. As loyal colonists, the Americans had long recognized parliament’s authority to legislate for the empire generally, as with colonial trade, but they had always maintained that the power to tax was a legislative power reserved to their own assemblies rather than a distant legislature in London. You’ll remember their slogan: no taxation without representation.

In making this argument, the colonials were objecting to being deprived of an important historic right: The English Bill of Rights of 1689 had forbidden the imposition of taxes without legislative consent, and since the colonists had no representation in parliament they complained that the taxes violated their traditional rights.

The British ended up repealing the tax, but in the Declaratory Act of 1766 they flatly rejected the Americans’ general argument by asserting that parliament was absolutely sovereign and retained full power to make laws for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” To the British, “no taxation without representation” was indeed a well-established right, but it was understood to mean no taxation without the approval of the British Parliament. And, they argued, it never literally meant—not for the Americans and not even for the overwhelming majority of British citizens—representation in that body. The colonists, like all British subjects, enjoyed “virtual representation” of their interests by the aristocrats that voted in and controlled parliament.

To the Americans, this was as absurd as it was unacceptable. Their commonsense notion of consent required actual representation—elected representatives of the governed making laws. So the declaration of the Stamp Act Congress—the first statement of the united colonies—argues that because the colonists were “entitled to all the inherent rights and privileges of his natural born subjects within the kingdom of Great Britain,” no taxes could be imposed without colonial consent. And since as a practical matter they couldn’t participate in a parliament thousands of miles away, the Americans concluded that this authority could only be vested in their local legislatures.

In 1767, the British government passed a new series of revenue measures (called the Townshend Acts) which placed import duties (external taxes) on a number of essential goods including paper, glass, lead, and tea—and once again affirmed the power of British courts to issue undefined and open-ended search warrants (called “writs of assistance”) to enforce the law. Asserting that the sole right of taxation was with the colonial legislature, Virginia proposed a formal agreement among the colonies banning the importation of British goods—a practice that quickly spread to the other local legislatures and cut the colonial import of British goods in half. So parliament eventually repealed those duties, too, except—in order to maintain the principle that it could impose any taxes it wished—for the tax on tea.

It was at Boston in the spring of 1770 that, tensions running high, British soldiers fired on a large crowd of protesters, wounding eleven colonials and killing five. The Boston Massacre, as it was quickly called, marked the final downturn in the relationship between Britain and the American colonies. By late 1772, Samuel Adams and others were creating new Committees of Correspondence that would link together patriot groups in all thirteen colonies and eventually provide the framework for a new government. They would soon form Committees of Safety as well to oversee the local militias and the volunteers who had begun calling themselves Minutemen.

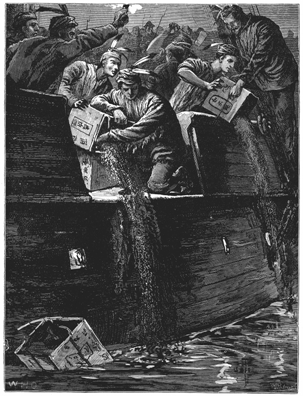

In December 1773, a group of colonists disguised as Indians boarded ships of several British merchants and in protest of British colonial policies dumped overboard an estimated £10,000 worth of tea in Boston Harbor. “The die is cast,” reported John Adams. “The people have passed the river and cut away the bridge. Last night three cargoes of tea were emptied into the harbor. This is the grandest event which has ever yet happened since the controversy with Britain opened.”

The British government responded harshly by punishing Massachusetts— closing Boston Harbor, virtually dissolving the Massachusetts Charter, taking control of colonial courts and restricting town meetings, and allowing British troops to be quartered in any home or private building. Richard Henry Lee wrote that these laws were “a most wicked system for destroying the liberty of America.” The American colonists, outraged by these violations of their first principles, their basic rights and the rule of law itself, called them what they were: Intolerable Acts.

In response to these acts, the various Committees of Correspondence banded together and planned a congress of all the colonies to meet in Philadelphia in September 1774. This united resistance gave rise to the Declaration of Independence and, later, to the United States Constitution.

Is it possible that Americans are waking up to the modern state’s long train of abuses and usurpations?

There is something about a nation grounded on principles. Most of the time, American politics is about local issues and those policy questions that top the national agenda. But once in a while, politics is about voters stepping back and taking the longer view based on the fundamental principles of the regime.

The opportunity and the challenge for those that seek to conserve America’s liberating principles is to turn the healthy public sentiment of the moment, which stands against the Left’s agenda of the unlimited state, into a settled and enduring political opinion about the nature and purpose of American constitutional government.

Only with this sure foundation can we go forward as a nation, addressing the great policy questions before us and continuing to secure the blessings of liberty.

Heritage

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Breitbart Is Here!

Total Pageviews

About Me

Conservative Sites and others that I Follow

- AA! Legislative Action America Again

- Ace Of Spades HQ

- America Speaking Out

- American Thinker

- Ann Coulter

- Atlas Shrugs

- Bare Naked Islam

- Big Government

- Big Hollywood

- Big Journalism

- Big Peace

- Bosch Fawstin

- Breitbart

- Breitbart TV

- Canada Free Press

- Colony 14

- Conservatives 4 Palin

- Constituting America

- Fox News

- Gateway Pundit

- Glenn Beck

- Heritage

- Hot Air

- Human Events

- Jews For The Preservation Of Firearms Ownership

- Mark Levin

- Mark Steyn

- Media Research Center

- Michelle Malkin

- National Black Republican Association

- National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation

- Natural Born Citizen

- New York Times

- Pajamas Media

- Patrick's World

- Politico

- Redstate

- Rush Limbaugh

- Sultan Knish a blog by Daniel Greenfield

- Tammy Bruce

- Tea Party Patriots

- The Black Sphere

- The Blaze

- The Daily Caller

- The Drudge Report

- The Heritage Foundation

- The Hill

- The Right Scoop

- Town Hall Patriots

- Townhall

- Truth Revolt

- Undead Revolution

- Voice in the Wilderness

- Walid Shoebat

- Wall Street Journal

- Washington Examiner

- Washington Times

- Yid With Lid

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(1598)

-

▼

March

(77)

- Liberty and Equality: Are They Compatible?

- Yes, It Can Happen Here

- Take Back Congress to Stop Obamacare

- Hey, Steve Jobs — Boycott Beck At Your Own Peril

- American Heroes Ready and Willing to Serve in Cong...

- A Black President, the Progressive’s Perfect Troja...

- The Wonderful Defiance of Sarah Palin

- This Guy Nails It! - In Defense of Sarah Palin

- Deadly Obamacare Kills Businesses, Jobs

- Democrats threaten companies hit hard by health ca...

- Is Scripture Statist?

- Warning: Subject to New Politically Correct Langua...

- Is a D.O.D. Insider Leaking Classified Information...

- How the Left fakes the hate: A primer

- Cui Bono?: When “Attacks” And “Death Threats” Are ...

- The Twisted, Tangled Branches of the Poisonous ACO...

- Hang ‘Em High: Obama’s Disgusting ‘Give Them Someb...

- Why It Must Be “Repeal And Start Over”

- The Tea Party protesters were boy scouts compared ...

- Don’t Get Demoralized! Get Organized! Take Back th...

- Princess Salerno

- Intolerable Acts and Tea Parties

- Out-of-touch Congress Sounds Our Clarion Call to T...

- “The Lesson of Phidippides”

- Obamacare Slaughter Rule is without Precedent

- Constitutional Law 101

- A Sleeping Nation

- GOP Senators Vow to Stop Reconciliation

- What's Arabic For 'You're No Atticus Finch'?

- Final 'reform' push: twisting arms

- Issa raises questions on Sestak

- Sen. Inhofe Says No Evidence of Virus on Drudge, S...

- Fix Medicare first — we already have health care, ...

- ACORN Defends Voter Drive Despite Workers Being Ch...

- Is the Declaration of Independence Still Relevant?

- Why Chuck Todd and the MSM Fear the Blogosphere

- Obama vs. Insurers and the People, Part 2

- Low-Tax Texas Beats Big-Government California

- Obama's Oscar

- Sarah Palin Talks Canadian Health Care, Baits The ...

- Reconciliation Is a Deceptive Distraction from the...

- Obama Draws Fire for Appointing SEIU's Stern to De...

- George Will Schools Reich On Healthcare and Today'...

- American-born al-Qaida member arrested in Pakistan

- Constitution? The MSM Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Const...

- Hey MSM, Obama Fans — About that Che Guevara Fetis...

- Eric Massa Unloads on Emanuel, Obama, and His Fell...

- Political Instability and the Coming Defeat of Oba...

- Overnight Thread: Steyn on Obamacare’s Kamikaze Ra...

- Clowns to the Right of Us, Jokers to the Right — t...

- The New Fascists, Part 4: The Marching Minions of ...

- The Left and Its Cheap ‘Racism’ Charge — the Last ...

- National security flip-flop: Obama to retreat on K...

- Sarah Palin A One Girl Revolution!

- Possible Action Today on the D.C. Opportunity Scho...

- Paul Ryan v. the President

- Republicans Plan Anti-Health Care Reform Bill 'Bli...

- The Friends of Barack Hussein Obama: the Castro Co...

- Subprime Mortgage Crisis Hits Whorehouses

- Free Speech as a Casualty of Intimidation

- Sarah Palin on the Jay Leno Show

- John Ziegler is wrong on Sarah Palin

- Study of Tea Party Activists Reveals Motivations o...

- Stopping the Runaway Congress

- The Bob Corker Bailout Sellout

- Unions: Forever War

- New York Times plumps GM, trashes Toyota, Never Me...

- What Is "Reconciliation" And Why Is It A Threat?

- ‘The Acceleration of Disbelief,’ Starring ‘Floor M...

- When Liberal ‘Journalists’ Attack, Real Americans ...

- Are You Packing Heat? Your Local Newspaper May be ...

- Seeing the World Through Nancy Pelosi’s Eyes

- More Guns, Less Crime

- The Left Is Underestimating Opponents Again

- Graft, Greed and Waste in State Government: New Me...

- Former Veep Goes Girly-Man, Has Hissy Fit in Pages...

- WaPo Ignores Tea Parties, Astroturfs the ‘Coffee P...

-

▼

March

(77)